proprietary software has failed: a community-driven open source security proposal

This is the text of a paper I delivered at UKSG November Conference 2024 on 2024-11-20 on the theme of 'Cybersecurity and Censorship'. It has been edited from the original to incorporate the accompanying presentation slides into the text and to insert additional detail and quotes.

In 1996 Post Office Limited, the Benefits Agency, and the IT company ICL teamed up to implement a swipe card system for payment of pensions and benefits from Post Office branch counters (Brooks and Wallis, 2020). The system used software called Horizon, a proprietary accounting system developed by Fujitsu. Though this initial project was a failure, the Post Office nonetheless pivoted the Horizon software to “transform its paper-based branch accounting into an electronic system covering the full range of Post Office services” (Brooks and Wallis, 2020). This new system went live in 1999 and between then and 2015, more than 900 Post Office employees were criminally convicted of theft and fraud based on evidence from the Horizon software. The Post Office continued to use the Horizon proprietary software even though both Fujitsu and the Post Office knew that the software contained bugs which created the appearance of financial shortfalls (Croft, 2024). As the Post Office’s board of directors wrote in their meeting minutes in September 2000, “[s]erious doubts over the reliability of the software remained.” (Brooks and Wallis, 2020)

Over the past eighteen months, multiple universities and libraries have been targeted in high-profile cyberattacks. In July 2023, the University of the West of Scotland’s systems were attacked by the ransomware gang Rhysida and their data auctioned off to the highest bidder (Cox, 2023). In February 2024, University of Wolverhampton, University of Cambridge, and The University of Manchester were all targeted on the same day with DDoS attacks from the Russian hacker group Anonymous Sudan (Woollacott, 2024; Lawson, 2024). In June 2024, Cambridge University Press & Assessment was attacked and their data published online by INC Ransom (Burhanuddin, 2024; Gardner, 2024; Rowsell, 2024).

The most high-profile and most culturally damaging attack was Rhysida’s attack on the British Library on 28th October 2023 during which 573GB of employees’ personal data was stolen and subsequently auctioned on Rhysida’s .onion site. The attack left dozens of core systems non-functional (British Library, 2024; Hamill, 2024). It’s been over a year and the British Library is still recovering from this attack at the heart of their infrastructure.

The British Library has been admirably open about the attack (while being aware of the security implications of publishing too much technical information) and published an 18-page review paper into how the attack happened and how they intend to recover (British Library, 2024). The review paper paints a picture of an IT department struggling with the amount of work, outgoing staff not being replaced, and knowledge of systems being lost when expert staff left: “[t]he Technology department was overstretched before the incident and had some staff shortages which were beginning to be successfully addressed.” The paper alludes to the outsourcing of IT functions to third-party providers and “[t]he increasing use of third-party providers within our network […] due to capacity and capability constraints within Technology and elsewhere in the Library”. It goes on to imply that entry to the Library’s network was gained through one of their “numerous trusted partners for software development, IT maintenance, and other forms of consultancy” (British Library, 2024). Peter Murray (2024) goes further in his analysis and points specifically to compromised credentials on Microsoft Terminal Services server, an outdated proprietary component of Windows Server 2008 and earlier.

An overstretched IT department with staff who weren’t being replaced and whose functions were increasingly outsourced to various third-party corporate providers is a familiar picture for UK Higher Education libraries. As university budgets were squeezed by both the impact of Brexit on student intakes and on Conservative Government cuts with no relief provided by the new Labour Government, university libraries have cut back on in-house technology in terms of both staff and infrastructure. Instead of investing in staff with expertise in library systems and core infrastructure, senior managers have instead chased short-term Silicon Valley fads like blockchain (Cilip, 2020), the metaverse (Larkin, 2023), and most recently large-language model generative ‘AI’ (Cilip, 2024). Library systems teams have been drastically reduced, in some cases to a single systems librarian and in other cases outsourcing library systems management entirely to equally overstretched IT departments or to third-party corporate vendors.

This corporate outsourcing of IT is only one part of a larger trend towards corporatisation in universities. In his overview of IT and information systems history in Canadian Higher Education, Mark Hayward (2023, p. 87) argues that “[t]he procurement, implementation and maintenance of IT as central to the core functions of the university has entailed the widespread adoption of techniques and ideas developed in the private sector” and this has led to a sense of “computational individualism” which disaggregates collective and collegial decision-making about IT in the university.

“While committees focused on teaching or research may be informed about major initiatives involving information processing infrastructure, decision-making is divided between individual users and full-time administrators depending on the scale and cost of the project. [...] This follows a logic that does not simply replace consultation with control, but rather entails the selective granting and protection of autonomy in some areas of academic life— research most notably—while enacting direct and highly-centralised forms of control in other areas.” (Hayward 2023, p. 91-92)

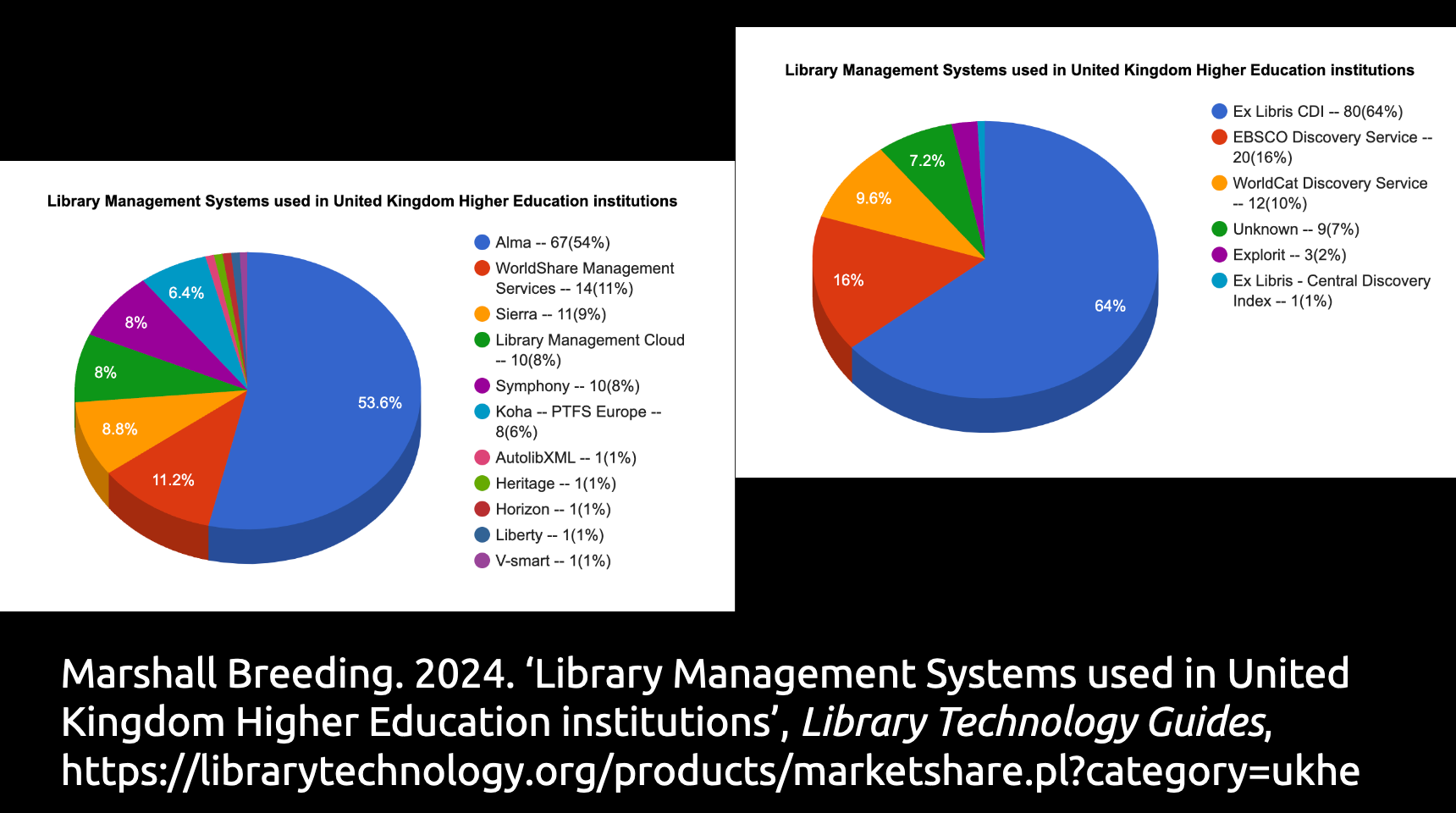

The ceding of technological autonomy and corporatisation of IT in UK Higher Education libraries manifests in a clear trend towards outsourcing to proprietary software providers and consultants. Marshall Breeding’s Library Technology Guides shows that the vast majority of UK university libraries outsource their library systems to corporate vendors.

Ex Libris dominates the market for both library management systems where Ex Libris Alma has 54% market share and for discovery indexes where Ex Libris Central Discovery Index has 64% market share. Other commercial vendors, OCLC, Ebsco, and Innovative Interfaces Inc. (which is owned by Ex Libris) follow close behind. Prior to the attack, the British Library used Ex Libris Aleph and Ex Libris Primo: there’s no indication that their on-premises installation of Aleph was a vector for the attack but it is nonetheless an outdated twenty year-old piece of software that should have been replaced years ago.

These proprietary products cost hundreds of thousands of pounds per year and yet they are anecdotally unpopular with users and staff members alike. We’ve all heard students and academics complain about how book reviews are prioritised to the detriment of all other materials in Ex Libris Primo and Central Discovery Index.

Despite university libraries across the UK being vastly different from one another in terms of collections and users, universities have squeezed their catalogues into the same piece of software, the same generic mould, in a way which fails to acknowledge or represent their true distinctiveness.

It’s worth mentioning that there has been some ethical divestment from these dominant Ex Libris products over the past year. Ex Libris Group is an Israeli company whose headquarters is built on land that used to be the Palestinian village of al-Maliha (المالحة) (Librarians & Archivists with Palestine, 2024). Since Israel began its genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza many universities have followed the recommendations of the BDS movement to stop investing in Israeli companies while Israel continues to occupy Palestinian land, run an apartheid regime of institutionalised discrimination, and commit genocide. Under pressure from their student bodies, Universitat de Barcelona, University of the Basque Country, Trinity College Dublin have all pledged to divest from Israeli investments while other universities like Goldsmiths, University of London, have adopted ethical investment policies that may extend to some level of divestment from Israeli companies like Ex Libris (@UniperPalestina, 2024; Henshaw, Kenny, & Conneely, 2024; @fatimazsaid, 2024).

Through this combination of external pressures and management decisions, universities and libraries have pushed themselves to a crisis point where, like the Post Office with its Horizon software, we are completely reliant on unreliable and insecure proprietary software: software provided by large corporations, software which libraries do not actually have meaningful control over, and software which, despite our misplaced trust, has failed time and time again. Our workplaces are built on a foundation of proprietary software which is unreliable, not liked by users or staff, and which fails to protect us from increasing numbers of cyberattacks. We collectively spend huge chunks of our budgets on bad software with the money flowing to the various private equity groups that own companies like Ex Libris Group or Overdrive Inc. when we could be investing that money in people and building in-house technical expertise. The one-size-fits-all proprietary outsourcing model leaves us all vulnerable to attack—if we all use the same proprietary software and attackers discover a weakness in one of our installations, then attackers discover a weakness in all of our installations. We instead need technical staff and infrastructures that can respond to our differing organisational needs and that can be adaptable to different threat models. In other words, we need to move away from the generic and towards the specific.

The solution is to move away from generic and costly proprietary software and to invest in our own technologies through open source software and community-led hardware and infrastructure solutions. We need to take back control of our systems and infrastructure from the corporations that have hijacked them for their own profit. Now that I’ve laid out the technical crisis facing UK universities and libraries, I want to briefly sketch out an alternative infrastructure model that could put security back in the hands of our libraries and be a better investment of resources than wasting money on proprietary systems.

The conceptual basis for this infrastructure model comes from the technical infrastructure that we’ve used in the Copim community. Copim is a community of people and organisations working to build infrastructures and models for open access monograph publishing. We’ve run two projects, COPIM itself and the ongoing Open Book Futures project, and both projects embody the principle of No Open Access Without Open Infrastructure (Steiner et al, 2024). Openness is a core ethical value of the project and so openness needs to be baked into everything we do, not just in terms of open access licensing but in terms of the software we create as part of the project and the technical infrastructure that we use to manage the project. We run as much of the project as possible using open source software and keeping control over our own infrastructure because we believe that open access and open source are intimately linked in the same struggle against exploitative commercial entities.

Copim maintains a couple of servers which run various pieces of open source software and we employ technical staff (like me) who can do both software development and systems administration. These servers run a suite of open source software for project management and project outputs. We run Nextcloud with ONLYOFFICE instead of Microsoft SharePoint and Microsoft Office; we run Hugo for our website instead of paying for website hosting from a commercial provider like Squarespace; we run Mattermost instead of Slack or Microsoft Teams; and we host our own project outputs including Thoth, an open metadata management and dissemination platform, and the Experimental Publishing Compendium, bespoke software that I developed to host a guide and reference to experimental publishing.

The servers cost us money and the salaries of staff members like me cost us money but it is a fraction of what we would pay for equivalent commercial software and it means that the project is investing in staff like me who are able to develop new software and new infrastructures for the open access community rather than giving money away to the private equity groups that own commercial software providers. This open source project infrastructure model has been so successful that my colleagues at Thoth will be offering Thoth Hosting for cloud hosting of the same Mattermost and Nextcloud project management infrastructure (Steiner et al, 2024).

This specific infrastructure model applies to our small project team of approximately 40 people but we can scale this DIY model up to apply to university libraries. Run a few servers hosting open source library software, divest from commercial software providers, and invest on in-house technical staff who can maintain those servers while contributing new software and infrastructures back into the wider library community. For larger libraries, you’d ideally want to run separate database servers, probably multiple separate database servers plus backups.

This also leads to various security advantages. On a basic level, open source software is simply more secure. There's often a false dichotomy drawn between 'openness' and 'security' but as cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier (1999) has said “[i]n the cryptography world, we consider open source necessary for good security; we have for decades. Public security is always more secure than proprietary security. It’s true for cryptographic algorithms, security protocols, and security source code. For us, open source isn’t just a business model; it’s smart engineering practice.” Open source software is more secure because it has to be. Proprietary software often relies on security through obscurity: it’s only secure because the source code is not public: if an attacker gains access to the source code, they gain access to all the underlying security mechanisms. The user is forced to accept what level of security the proprietary provider is willing to develop. By contrast, open source software source code is open—open to customisation, open to modification, open to review—and so security mechanisms have to actually be cryptographically secure to everything except the key. This is known as Kerckhoffs’ principle after the cryptographer Auguste Kerckhoffs: a cryptographically-secure system should be secure even if everything except the key is public knowledge. An adversary could know exactly how the lock works and yet still not be able to open it without the key. Openness is security.

Apart from open source software being more secure, there are security advantages in the infrastructure model itself. Not only does it give the library itself control over its own security through its own firewalls and so forth but it means that you can build security into the infrastructure. For example, you could air gap database servers from the external internet so that only the application servers can connect to them. This would provide a security buffer against external attackers looking to extract and ransom user data. If you wanted to push it further, you could separate user data and borrowing data so that they don’t live together in the same database but are instead brought together in the application layer by either the library management system or the library catalogue. This would mean that even if someone got hold of one set of data, they couldn’t identify what books someone had borrowed from either set of data in isolation. With various US states increasingly censoring LGBTQ library collections and US enforcement agencies interrogating borrowing data for who took out “banned books”, this would be a valuable technical barrier to protect the privacy of your library users.

So far this is what I’d call an individualised infrastructure model geared at a single library running their own servers and open source systems. But we can push this even further by thinking along the lines of collective and community-driven library systems installations. Instead of each library running their own servers, a group of university libraries instead invest in a collective multi-tenant infrastructure with each server hosting multiple versions of library applications.

This is the basic model for how commercial providers run their servers: your library’s instance of Ex Libris Alma isn’t running on its own dedicated server, your version is running on a server that’s also running several other universities’ versions of Ex Libris Alma. The difference here is that libraries themselves would be collectively running the servers hosting their infrastructure. This could be achieved through a collectivised funding model whereby the libraries come together to pay money into a collective pot that funds the server hosting and pays the staff looking after the servers and systems. This wouldn’t be dissimilar from how Jisc operates as a non-profit company to provide the shared technical infrastructure of the Janet broadband network to all UK universities and further education institutions. This would just be on a smaller scale and focused on library systems provision.

This is a very cursory sketch for this potential infrastructure model and there are bound to be technical and logistical hurdles that would need to be addressed but I think the basic premise—multi-tenant servers collectively owned by libraries coming together to drive community development of open source library systems—is an eminently achievable alternative to the proprietary systems and proprietary infrastructures that are currently letting down libraries and universities across the country. Collectivisation is how we will address the technical challenges facing our institutions. This must be collective work, as Hayward (2023, p. 93) argues:

“this project must not be limited to the work of committees; labour unions, student unions, and community groups are all organisations who have a stake in transforming the political ecology in which IT in higher education is designed, adopted and used. Common cause with other movements working towards the democratisation of information and technology (e.g. movements on- and off-campus supporting open access, or the ‘right to repair’) should also be sought out for shared areas of concerns, but also strategies for building and maintaining national and international advocacy and policy development.”

By divesting from third-party proprietary software companies, we could redirect budgets away from expanding the profits of private equity companies and towards investing in people and software in our community working for community good. This is not only a more ethical approach but a more secure practical approach that would give us back control over our own systems in order to better protect them from the multiple threats currently facing libraries and library users.

references

Acampada per Palestina Barcelona🇵🇸 [@UniperPalestina]. 2024. ‘🚨🚨HISTORIC WIN🚨🚨 📣🇵🇸UNIVERSITY OF BARCELONA PASSES MOTION TO CUT TIES WITH ISRAEL📣🇵🇸 Https://T.Co/J6Ouj2N1De’. 𝕏. https://x.com/UniperPalestina/status/1788219726834917862.

Bowie, Simon. 2024. ‘The British Library Hack Is a Warning for All Academic Libraries’. Impact of Social Sciences (blog). 19 March 2024. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2024/03/19/the-british-library-hack-is-a-warning-for-all-academic-libraries/.

British Library. 2024. ‘Learning Lessons from the Cyber Attack: British Library Cyber Incident Review’. London, UK: The British Library. https://www.bl.uk/home/british-library-cyber-incident-review-8-march-2024.pdf.

Brooks, Richard, and Nick Wallis. 2020. ‘Justice Lost in the Post’. Private Eye: Special Reports. Private Eye. https://web.archive.org/web/20240116130930/https://www.private-eye.co.uk/pictures/special_reports/justice-lost-in-the-post.pdf.

Burhanuddin, Omar. 2024. ‘University Publishing House Faces Cyber Attack’. Varsity Online. 2 July 2024. https://www.varsity.co.uk/news/27854.

Cilip. 2020. ‘CILIP’s Blockchain Briefing’. 27 February 2020. https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/Blockchain20.

Cilip, 2024. ‘AI Hub’. Accessed 19 November 2024. https://www.cilip.org.uk/ai.

Cox, Auryn. 2023. ‘Scottish University UWS Targeted by Cyber Attackers’. BBC News. 27 July 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-66327336.

Croft, Jane. 2024. ‘Hundreds of Post Office Victims to Get Access to New Compensation Scheme’. The Guardian, 30 July 2024, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/article/2024/jul/30/victims-of-post-office-horizon-scandal-compensation-scheme.

Fatima [@fatimazsaid]. 2024. ‘🚨 BREAKING: Following 6 Months of Protest and 5 Weeks of Occupation, Goldsmiths University Management Have Conceded to @Gold4Palestine Demands to Divest from Israeli Occupation 👏👏👏 This Is a Huge Victory! More Details in the Thread below 👇 Https://T.Co/maWodzhZ9A’. 𝕏. https://x.com/fatimazsaid/status/1786416204476756360.

Gardner, Gemma. 2024. ‘Investigation Launched after Cybersecurity Incident at Cambridge University Press & Assessment’. Cambridge Independent. 6 July 2024. https://www.cambridgeindependent.co.uk/news/investigation-launched-after-cybersecurity-incident-at-cambr-9373519/.

Hamill, Jasper. 2024. ‘British Library Reveals £400,000 Plan to Rebuild after “Catastrophic” Ransomware Attack’. The Stack. 21 August 2024. https://www.thestack.technology/british-library-ransomware/.

Hayward, Mark. 2023. ‘System Lag: Re-Building the Collective Governance of Information Technology’. New Formations 2023 (110): 78–94. https://doi.org/10.3898/NewF:110-111.05.2024.

Henshaw, Kate, Ellen Kenny, and Stephen Conneely. 2024. ‘Breaking: Trinity to Work towards Total Divestment from Israel in Unprecedented Win for BDS’. Trinity News (blog). 8 May 2024. https://trinitynews.ie/2024/05/breaking-trinity-to-work-towards-total-divestment-from-israel-in-unprecedented-win-for-bds/.

Larkin, Marilynn. 2023. 'Demystifying the Metaverse: What Academic Librarians Need to Know' Library Connect. 8 February 2023. https://www.elsevier.com/connect/demystifying-the-metaverse-what-academic-librarians-need-to-know.

Lawson, Eleanor. 2024. ‘University of Wolverhampton Confirms “Cyber Security Incident”’. BBC News. 22 February 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgrlljz2pv5o.

Librarians & Archivists with Palestine. 2024. Exposing Ex Libris. Librarians & Archivists with Palestine. https://librarianswithpalestine.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ExLibris1Color.pdf.

Murray, Peter. 2024. ‘Learnings from the British Library Cybersecurity Report’. Disruptive Library Technology Jester. 9 March 2024. https://dltj.org/article/british-library-cybersecurity-report/.

Rowsell, Juliette. 2024. ‘University of Cambridge Publishing Arm Hit by Cyberattack’. Times Higher Education (THE). 3 July 2024. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/university-cambridge-publishing-arm-hit-cyberattack.

Schneier, Bruce. 1999. ‘Crypto-Gram: September 15, 1999’. Schneier on Security. 15 September 1999. https://www.schneier.com/crypto-gram/archives/1999/0915.html?ref=opensauce.simonxix.com#OpenSourceandSecurity.

Steiner, Toby, Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei, Hannah Hillen, and Brendan O’Connell. 2024. ‘A Growing Network of Open Infrastructures and Federated Services with Thoth’. Copim, May. https://doi.org/10.21428/785a6451.92d1c71e.

Woollacott, Emma. 2024. ‘UK Universities Left Scrambling in Wake of Cyber Attacks’. ITPro. 21 February 2024. https://www.itpro.com/security/uk-universities-left-scrambling-in-wake-of-cyber-attacks.